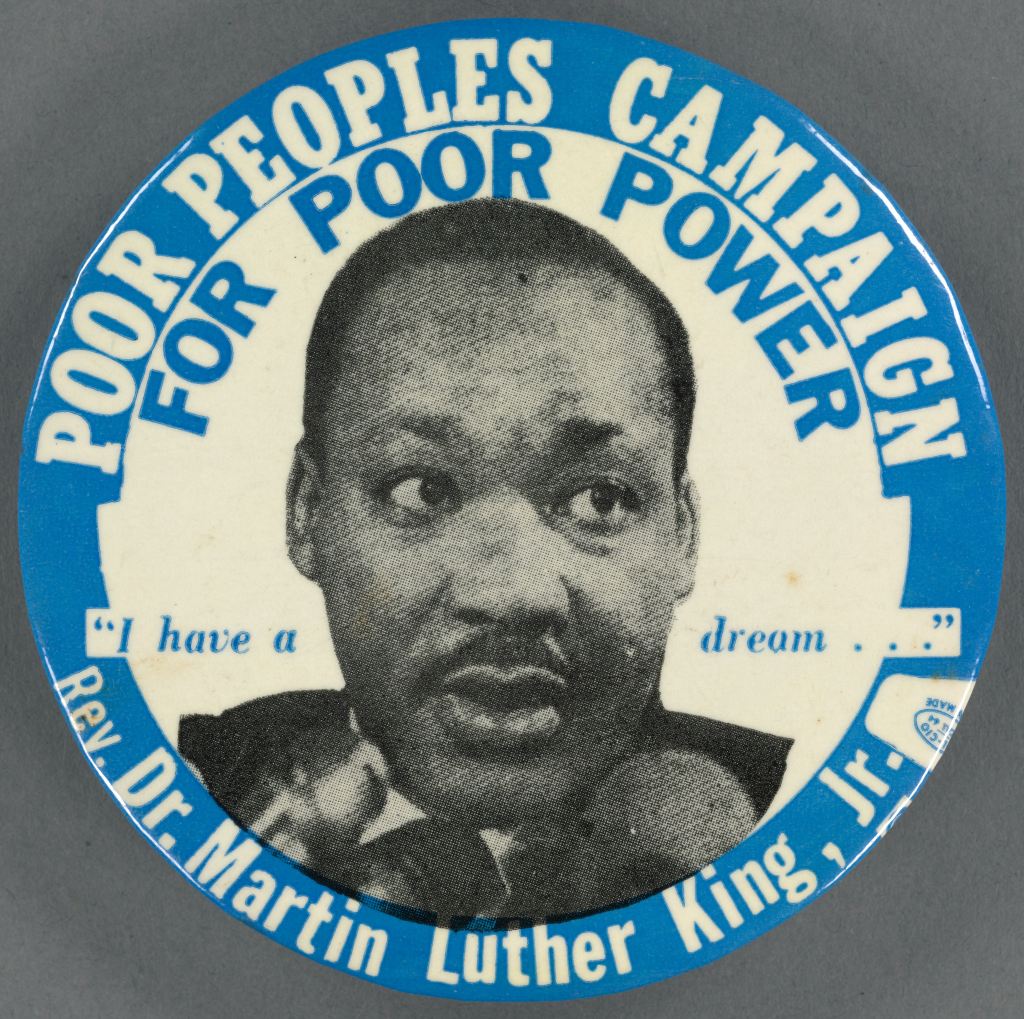

I’m using the title White Wife/Blue Baby for my forthcoming memoir. When the phrase first hit me, my psychological hair stood on end. I married across the color line in ‘68, and our daughter was born not getting enough oxygen, two facts with ambulance sirens attached to them.

When I first referred to my title in an email, I discovered that white wife is also a porn category. Invitations to purchase biracial erotica started piling up. The concept was not a white woman whose husband is Black, but a prim blonde lady who breaks her marriage vows because she suddenly can’t resist sex with a huge Black man. I opened the first one by mistake, not realizing what it was, accidently insuring that it would keep coming. For unknown reasons, it has finally stopped, though this blogpost will probably start it again.

What I could surmise from the email titles, and what I knew from watching pedestrians stare at my crotch when I was out with my then-husband, was that interracial sex was the most breathtaking transgression Americans could imagine. Early on, I would quickly and furtively check that my jeans were zipped. But they always were, and the problem wasn’t my clothing. Instead, the zone of privacy to which we are normally entitled walking down the street had been ripped away — privacy you don’t know you have until it’s gone.

I’m staying with the title, not because I want to do battle with Big Porn, but because while I was married to a Black man, I saw things and experienced things that a white person would have a hard time learning any other way. Things that went far beyond crotch-glancing. Traffic stops for nothing. Chicago cops whose stares said you should die. Apartments that had all just been rented.

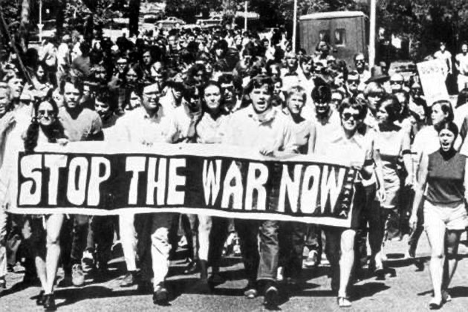

I call on other white partners, especially those who crossed the line decades ago, when a mixed couple was rare. It’s time to talk out loud about racism’s ability to lower you into a concrete bunker with no windows and no doors. Young white people have joined Blacks in the streets to call out racism. Let’s write about it. Let’s shout about it.