When I met the father of my children, he was just starting a job for a new project at the Black YMCA in Chicago. (Yes, Y’s were segregated.) Jobs Now aimed to get corporations to hire Blacks. I was surprised that the focus was on jobs, when, in the late sixties, it seemed to me that jobs weren’t that hard to get. (They weren’t if you were white.) Why didn’t the Y focus on desegregating schools or neighborhoods? I knew about as much history as the average white suburbanite, unaware that when Chicago’s factories moved to the suburbs, all their Black workers were left behind. Without these massive, unionized industries and the small businesses that catered to their workers, the city’s Southside and Westside economies collapsed. American sociologist William Julius Wilson estimated that the Black working class Chicago neighborhood of North Lawndale lost 75 percent of its businesses from 1960 to 1970.

Later, doing research for my memoir, I read what the NAACP’s then assistant secretary Walter White wrote in 1919 about the waiters’ strike in Chicago. Black waiters were persuaded to join the union, leave their jobs and walk the picket line, but when the strike was settled, whites went back to work for better wages, but Black waiters were not rehired. A job as a waiter was safe, indoors, and did not involve slaughtering animals or coming close to a cauldron of liquid steel. You worked right next to white people. For a while.

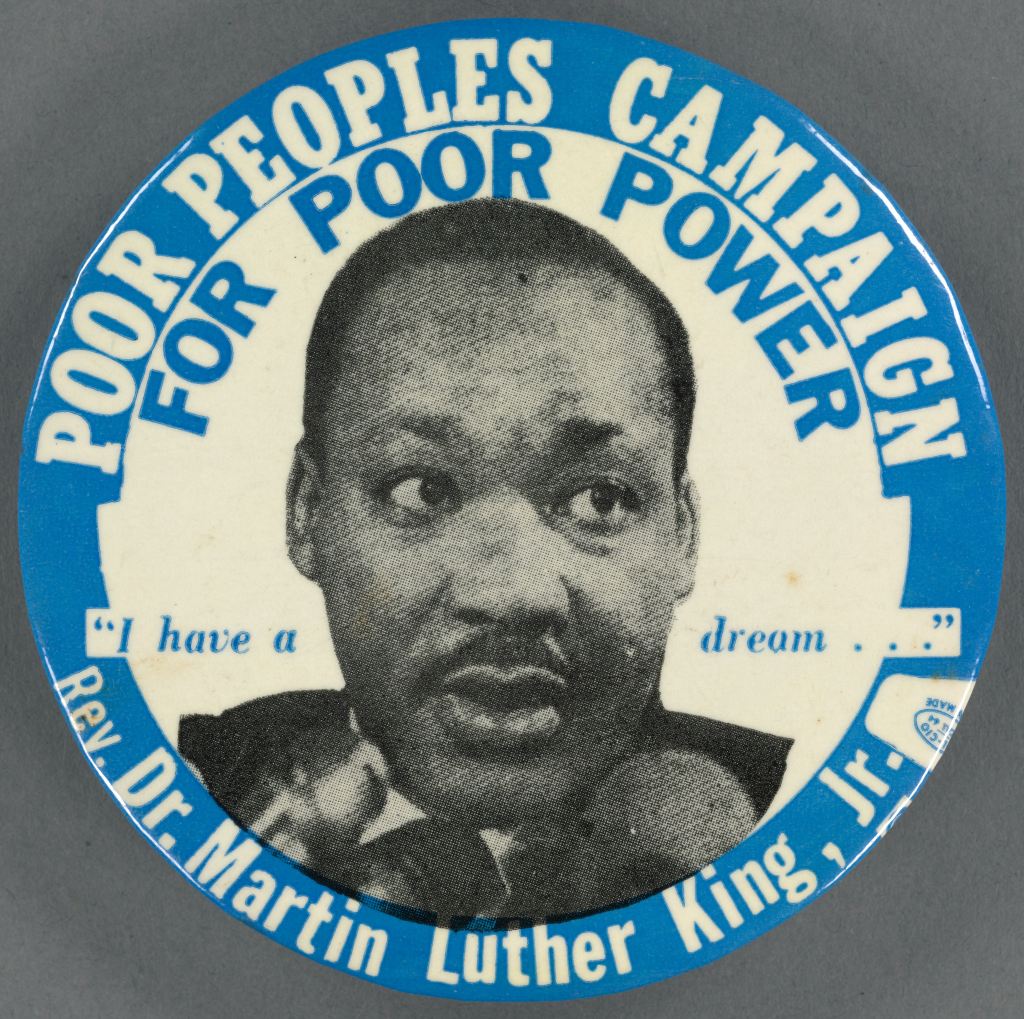

We could pile on other examples, of course, but the decision the Supreme Court rendered this summer insisted that a little more than 40 years of affirmative action had been enough to rectify four hundred years of oppression.

The conservative justices wanted to consider what happens when people today, now, really want to get their kids into a prestige college. It’s hard to care about how things are going for the ex-waiters’ great grandchildren or the laid off factory workers’ offspring when your own social mobility is on the line. The urge to move up past other people, climb higher, to be let in where others are excluded, is a deep-seated human desire. But it’s not us at our best.

#affirmative action #racialequity #chicagohistory