When I started dating across the color line in 1967, I was pretty sure that I could deal with Chicago racism. Losing my father to drink and being sexually assaulted by my pastor were probably my fault, so being disapproved of – well, so what?

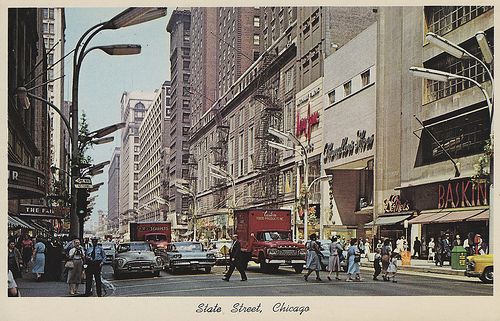

One night my boyfriend Emmon borrowed a car. On the L, my far Northside apartment was an hour from where he lived a little south and west of the Loop at the Young Christian Workers House. He and a bunch of other young, serious-minded Catholic guys were going to save the world from segregated labor unions. They did their best.

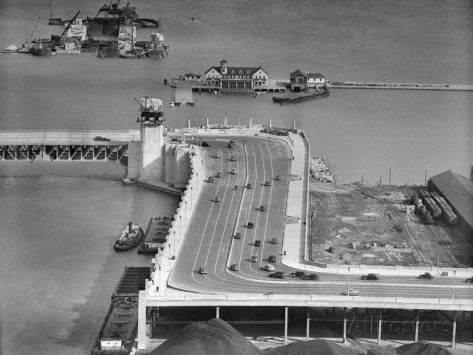

The dented-up VW bug we picked up from his friend had a sketchy coat of flat black paint. The upholstery, if you could call it that, had the smell of oily dust, the kind that only old cars have. Together now for a couple of months, we were headed toward Old Town, our leftie hang-out, speeding along and feeling the glorious cool breeze through the open windows. It was as if Emmon had walked up to me through the gray blur I’d been living in and started making me laugh. I almost didn’t know what to do with the happiness. But as we cruised north on South Shore Drive, what had started as a grumpy conversation was becoming an argument:

“You said you’d pick me up at seven,” I complained.

Emmon turned toward me and whispered tensely, “I never said that!”

He turned back to the road just in time to see that we were headed into the ninety degree turn that the Drive, built as a scenic parkway in the ‘30’s, was famous for. Frantically, he heaved into the turn, narrowly missing the concrete barrier while a great gust of wind came off the Lake and broadsided the car.

In an instant, the road noise stopped. I was puzzled by the silence, unaware that we were airborne. My mind switched to the curious slow motion that goes with an emergency. The VW had flipped and come down on its roof. Now the car was spinning sideways across four lanes. Sparks appeared next to my eyes — angry, yellow sparks that cracked and popped. I could smell the singed pavement. The screeching, howling, grind of metal on concrete became a dead-pan thought:

“This is the loudest sound I have ever heard.”

Finally, the spinning stopped and everything was silent again. With no more sparks, I could only stare into the blackness and smell the burnt metal. I didn’t know where Emmon was. Dread swept into my heart. Then he reached over and put his hand on mine. His touch brought back all his tenderness and teasing, the way he snickered at my crooked baby toe.

We creaked open the doors and crawled out. Now I was shivering. Another car had stopped to see if we were all right.

“That was some spin out!” exclaimed the long-haired young white guy as he walked quickly toward us, “Are you okay?”

“Hey man, thanks for stopping,” Emmon said.

He guided me to a safe spot, then walked back toward the VW where it sat in the far right lane.

“I bet we can turn this thing over,” he called. His tone had gone from shaky to bravado.

The hippy guy ambled to the side of the car, sizing it up, then stood next to Emmon.

“One. Two. Three!” they shouted in unison.

They gave the car a good heave, and, to my amazement, it rolled and lurched and sat upright.

“Why on earth does Emmon think turning the car over is a good idea?” I said to myself. “Maybe to make it easier for the tow truck.”

“Okay!” yelled the young guy, pleased with himself, dusting off his jeans.

Emmon and the Good Samaritan shook hands before he went back to his car and drove off.

“Let’s go,” Emmon said, motioning me toward the VW.

“What? We can’t go. We have to wait for the police!”

We’d almost been killed and the roof of the car looked like it was still boiling. We’d have to tell the police that we had been arguing. The cop would frown as he took notes. It would be like going to confession. I’d feel guilty, embarrassed, but we had no choice.

“We have to get out of here,” Emmon insisted.

I stared at him. Apparently, Emmon had no plans to tell the police that there’d been a crash, much less why it had occurred. But in my world, auto accidents weren’t secrets. You can’t just act like nothing happened. We’d have to wait for a cop to come along.

“What if the car isn’t drivable?” I asked, stalling for time. “We could get hurt.”

“We’ll go find someone who can look at it,” he said, guiding me into the passenger seat.

Cinders trickled off the door as Emmon slid gingerly behind the wheel. When the engine miraculously started, he rolled carefully out onto the Drive. I held my breath, waiting for wheels or bumpers or at least the rearview mirror to fly off. Our mouths were full of grit.

How could Emmon want to escape the help we needed from the police? Each time we had encountered them on the street, they had glared at us menacingly in a way I’d never seen before. But certainly the police would drop that sort of thing in an emergency. I still needed to believe that the world beyond my bashed-up childhood was more or less put together right, and that things like racism only went so deep.

By the time we married (1968) and had a child (1969), we’d been kicked around by a series of events that were as shocking as our auto accident. I’d learned to fear the police as Emmon had shown me, to be ever vigilant, even while deep in conversation. Whenever we walked down the street together, we filtered out all the ugly looks, focusing only on a certain kind of anger, then scanning bodies for the bulge of a gun. But even though I’d learned some street smarts, it took many more years for me to understand the hidden power of racism. Because learning about that meant learning about myself. Understanding racism is like understanding human nature. I’m still working on that.